by ALLIE BISWAS

Afruz Amighi (b1974, Iran) grew up in New York City and studied political science at Barnard College at Columbia University before taking her MFA at New York University several years later. The majority of her work has focused on large-scale installations and sculptures: geometric and cage-like constructions made from steel, fibreglass mesh, Plexiglas and chain, that hang from the ceiling or stand upright on the ground in a cluster, and are often cast in light. For No More Disguise, her first New York solo show with the Leila Heller Gallery, which follows her display at the gallery’s Dubai space last year, Amighi presents a series of six drawings accompanied by six corresponding sculptures. As well as marking the first presentation of her drawings to date, the exhibition also debuts a smaller scale not seen in Amighi’s previous work.

Allie Biswas: This exhibition is a change in direction for your work – you are showing drawings for the first time.

Afruz Amighi: I think in terms of what you’re seeing, this is a big turn for me. For the past 15 years, I have been doing very architectural-based work. So, previously, drawing was always a means to a sculpture. It was always in the form of a preparatory drawing. The drawing was always limited by what I thought I could realise in the third dimension.

AB: A remnant from this previous approach to drawing is seen within these new works, in the form of the paper you have used.

AA: The graph paper was around because of all of the mechanical drawings I had been making for my sculptures. This time it was really amazing to draw without the constraint of thinking about sculpture, or thinking about a show that the work would be placed in. These drawings are a product of those circumstances, and, also, this is the first time since college that I have worked with the figure.

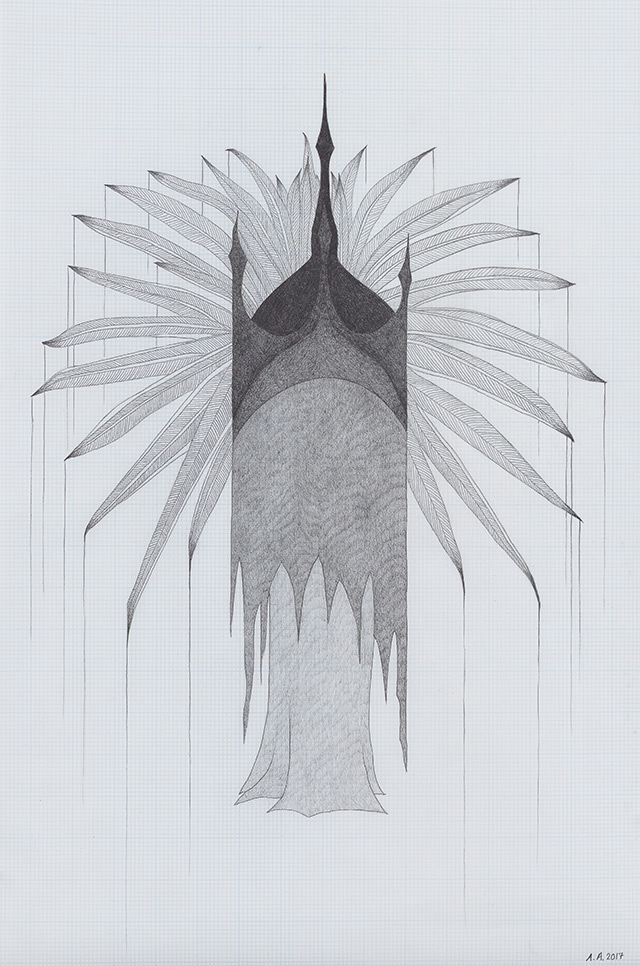

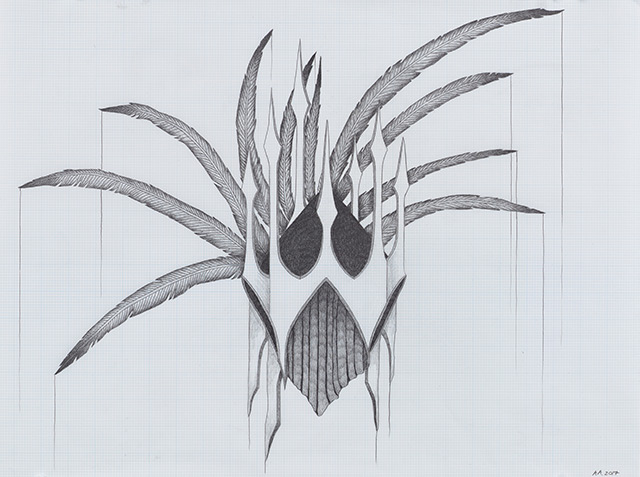

Afruz Amighi. Emperor’s Headdress (drawing), 2017. Graphite on graph paper, 24 x 16 in (61 x 41 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

AB: Let's talk about the first drawing in the series, titled Emperor's Headdress (2017). Was this the first drawing you made?

AA: Yes. And I think it's a little more static than the others. This is the first character in the court of medieval characters that are depicted in these six drawings; the first character that I came up with for the show. It started out as a portrait of a friend of mine. I was thinking, if he were to wear a crown or a headdress that would cover his face, and adorn him, what would it look like? This is what I came up with. It was like an experiment. I gave my friend the original drawing, so what you are looking at is actually the second drawing.

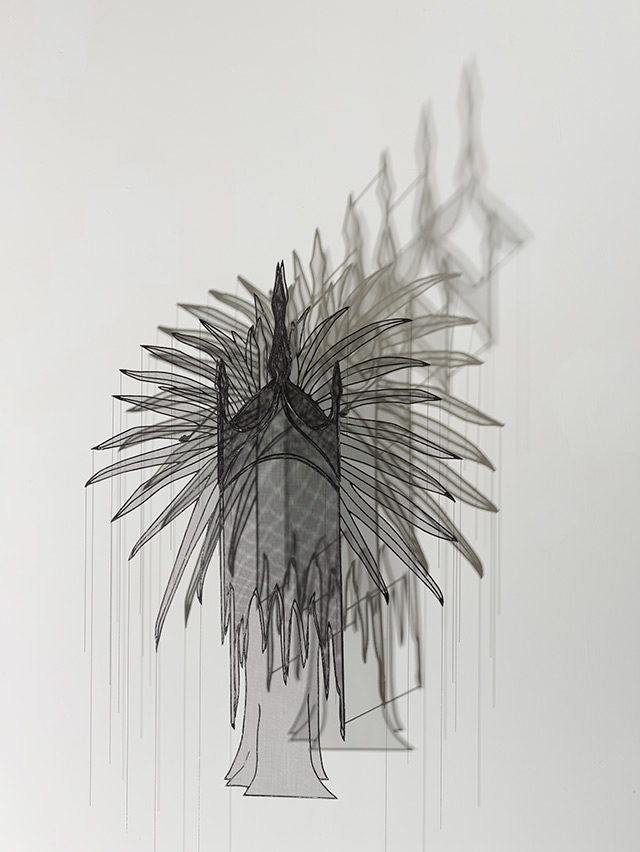

Afruz Amighi. Emperor’s Headdress, 2017. Steel, fibreglass mesh, chain, light, 50 x 39 x 14 in (127 x 99 x 36 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

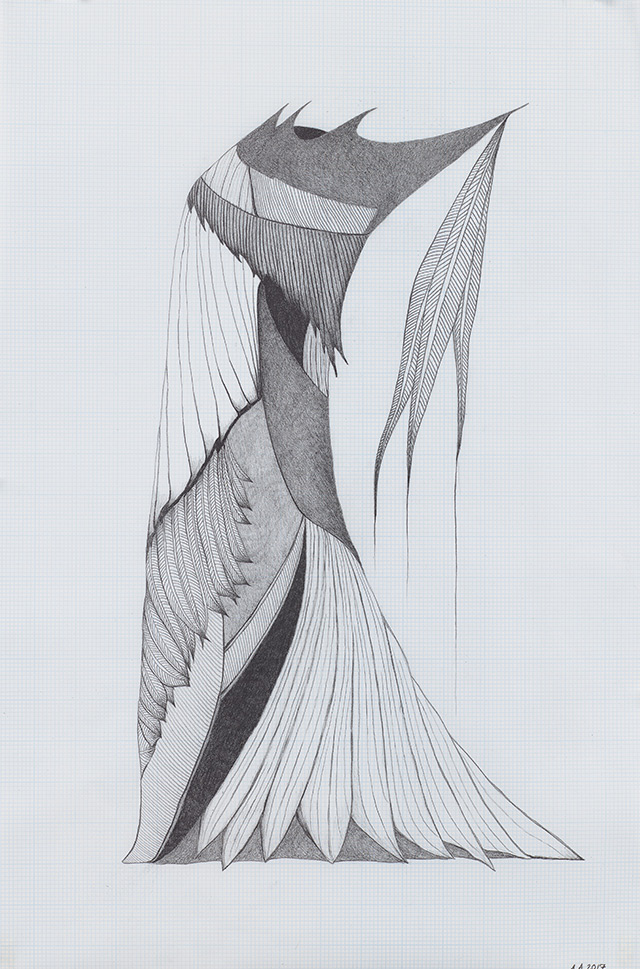

AB: How did the other drawings in the series follow?

AA: Since I made this headdress for an emperor, I thought that I needed an empress. I remember thinking, who can I cast out of the people I know in my life as the empress? The more I looked for someone, the more I realised that I was making an archetype, which was an ideal that women could aspire to, but that no woman could actually embody. So the empress, as well as the emperor, is a bit of a detached character. She is someone who is above the fray, in a bit of an inhuman way.

Afruz Amighi. Headdress for an Empress (drawing), 2017. Graphite on graph paper, 24 x 16 in (61 x 41 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

AB: In what context did these works evolve? Why did you turn to this notion of devising characters?

AA: All of these drawings were made right after the election here in the US. I had been in a state that I hadn’t experienced for many, many years – one of artistic malaise. I felt no urgency and I felt pretty irrelevant. So, I was surprised by how quickly my reaction to the election came to the surface in terms of an artistic, tangible expression, as it usually takes time for experiences to be assimilated – they may not come out for years. But this was very sudden for me. I felt that all of these characters – of people in my life but also of people in the world – were people I wanted to introduce. There are more inside, waiting to come out, but these are the first six.

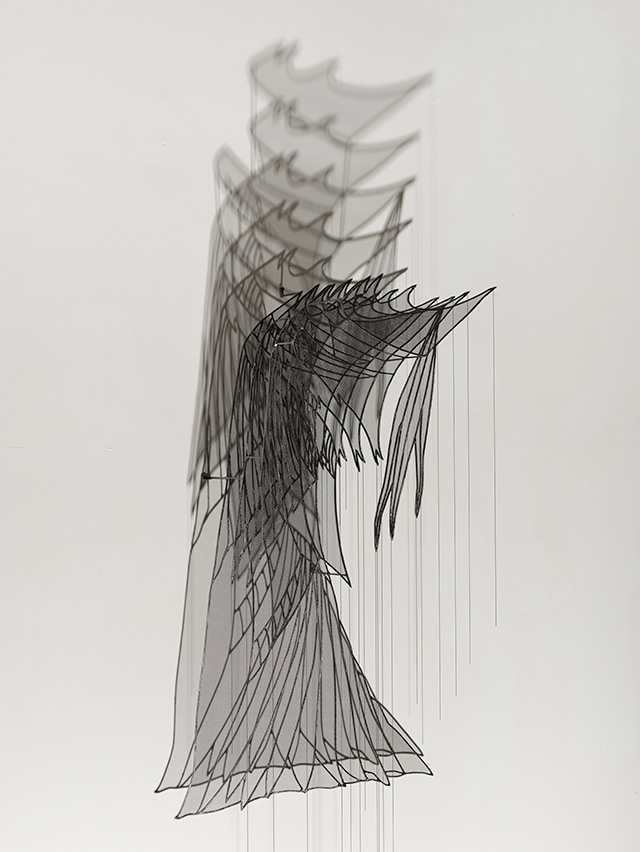

Afruz Amighi. Headdress for an Empress, 2017. Steel, fibreglass mesh, chain, light, 46 x 28 x 14 in (117 x 71 x 36 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

AB: The figures that you are presenting all have a darkness about them, both in terms of their monochrome aesthetic and their configurations. At times they look quite menacing. Were you aiming to signal something ominous through them?

AA: I think there is a huge group of people that can fall under the anti-Trump umbrella. My feeling about the election is that it exposed a civil war that has never ended between the north and the south, or whatever divide you want to say there is – black/white, male/female. There is a divide in this country and it has been glossed over with this and that reform, and it was there under Obama. It’s not like he was some kind of saviour. Now that perhaps the ugliest phase of capitalism has come to be the president, I feel like people from the left, the right or the centre, feel very emboldened to show what they think and say what they think, regardless of the atmosphere it creates and the violence it creates. I see this moment as an earthquake that happened and these creatures are coming up from what was before a subterranean existence and is now more of an open existence.

I was thinking of the processions of people with headdresses that we have in this country. In New Orleans, there is Carnivale and Mardi Gras. You think of the Ku Klux Klan marching through the south, even in the 80s and 90s.

I wanted to make a procession of characters that embodied both good and bad, so there is some kind of dichotomy within each character. There isn’t a clear distinction in terms of where they fall on the moral compass.

AB: You made reference earlier to “a medieval court of characters”. Was this historical period of interest to you when you were thinking about these works?

AA: I’m very drawn to European medieval art, and I think that, in terms of the aesthetic, there are a lot of art deco and medieval references here. But I have to emphasise that making the drawings was a very intuitive process and I wasn’t informed by any of those things. If anything informed the work, I would say that I was doing a lot of reading on US history, the Indian wars and the latter part of the period of slavery in this country. That’s what was on my mind, and so I think the feathers you see are very direct references to the Native American aesthetic, in terms of our history of enslaving people and making a lot of money from those people.

AB: How has your relationship with your own history developed as your work has progressed over the past 15 years? Your earlier work was particularly focused on these personal connections.

AA: When I was first making work, I was very interested in questions of identity. I was very much looking to the Middle East, to Iran in particular, in terms of history and culture. At the time, I was much younger, and I didn’t realise that identity is not a fixed thing, and that it shifts as you change, as well as the way in which you see yourself in relation to the world. So my work shifted just as my identity references shifted. I got to the point where, after looking at the Middle East for a long time, I started looking at medieval Europe – Spain in particular – and I was really interested in that period of history. Then, after the recent election, I thought, you know what, I feel like it’s really important for me to assert my American identity right now. I am an American. I grew up here. I do think that Iranian-American is a weird hyphen and in some ways more of a marketing tool. It’s a bit fraudulent for me. I feel more like a New Yorker than anything else. Anyway, I knew that I needed to get more of my American history together, so that’s when I started to read up on this subject. This exhibition is a direct result of that, and I think I’m going to be here – thinking about this kind of history – for a little while.

AB: After making these drawings, you made six corresponding sculptures, reversing the previous relationship that you had set up between your drawing and sculpture: this time the sculpture is led by the drawing.

AA: After doing the drawings, I decided to see if I could bring them into 3D.

AB: How do the figures evolve as the medium changes?

AA: These are still characters for me, in the sculptural format. But I definitely felt like all of them became the characters in a different way – they revealed different parts of themselves in 3D.

Afruz Amighi. Warrior’s Headdress (drawing), 2017. Graphite on graph paper, 18 x 24 in (46 x 61 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

AB: Each sculpture is layered, with the first section being positioned closest to the wall, and the following layers being placed on top, so that the work protrudes from the wall. Is there a hierarchy in terms of which sections of the sculpture were given the most visibility?

AA: I was really thinking a lot about that. Out of habit, I was trying to follow the drawing. So, where I was making lots of dark lines with the graphite on the paper, I was thinking, let me make all these layers on this part of the sculpture to get that same feeling. But if you look at the last sculpture I made next to the drawing, you can see that it is the loosest of all of them. In that work, I kind of let go a little bit of trying to get the same gradations of the black.

Afruz Amighi. Warrior’s Headdress, 2017. Steel, fibreglass mesh, chain, light, 38 x 44 x 14 in (97 x 112 x 36 cm). Photograph: Studio Suarez. Copyright 2017. Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

AB: What is the black meshed material that you have used to form each sculpture?

AA: It's mosquito netting, which is made out of fibreglass. I first encountered this type of netting through the construction work that is seen all over New York. When they put up the frame of the building, they wrap it in this fibreglass material, so that any concrete or rubble will be caught, preventing it from falling on passersby. I always thought it was beautiful, so I ordered rolls and rolls of it and it sat in my studio for a good part of a decade. I didn’t know what to do with it. Then about two years ago I started using it. What you’re seeing in these sculptures is the netting adhered to steel frames that I cut and welded together, with my assistant. The third material in each sculpture is the chain, and the fourth material is the light. Light has always been the constant in my work. It transports me, and it turns the object into more of an experience.

AB: Although your previous work has been based on personal history, this show feels distinctly personal.

AA: It’s very personal work – the most personal body of work that I’ve made. The previous work was about absence, and I wasn’t there to experience the events that I was discussing in my art in a very academic way. This current work is a shift. I am talking about presence in this work.

• Afruz Amighi: No More Disguise is at Leila Heller Gallery, New York, until 28 July 2017.