Royal Academy of Art, London

23 September – 10 December 2017

by JANET McKENZIE

Jasper Johns: ‘Something Resembling Truth’ presents more than 150 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints in the first comprehensive exhibition of the pivotal American artist’s work to be held in the UK in 40 years, revealing him to be one of the most influential and important living artists to emerge in the 20th century. Acutely receptive to the changes in society and wider political and social concerns, his iconic flags, targets and maps from the 1950s are immediately recognisable.

The extent to which Johns (b1930, Augusta, Georgia) absorbed influences from the history of art, as well as poetry and music, and the extent to which he has influenced other artists from the late-50s onwards cannot be overestimated. After the solipsistic nature of abstract expressionist art of the postwar era, Johns’s work in the late-50s can be seen as international symbols, instantly recognisable from the position of any country and any culture. His art represents an accessible, egalitarian language indicative of the collective spirit that found expression in music festivals, the civil rights movement, sexual liberation of the 60s, the advent of feminism and the opposition to the Vietnam war.

[image7]

Abstract expressionism, colour field and action painting were the American contributions to modernism. By the mid-50s, with the bourgeois acceptance of abstract art, a new trend developed that, in 1958, Art News described as neo-dada, “unaggressive ideologically but covered with aesthetic spikes”, in stark contrast to the emotional drama and elegance of abstract expressionism. Johns became familiar with the work of Marcel Duchamp in the late-50s and met him in 1959. In the 60s Johns wrote three short essays on Duchamp’s work, observing in 1969 that he, “was the first to see or say that the artist does not have full control of the aesthetic virtues of his work”. Johns also exhibited drawing and printmaking with painting disrupting the traditional hierarchy that placed painting above other media.

[image6]

Johns’s first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1958 was a huge success; three paintings were acquired for New York’s Museum of Modern Art. During the 60s, with Robert Rauschenberg, Johns introduced everyday objects on to the canvas, enabling the elements of chance and irreverence to undermine the aura of the masterpiece. More importantly, the use of quotidian materials and readymades gave the work an archetypal appeal and enabled the artist to capture the immediacy of fleeting experiences that conjure associations in the mind on a deeper level.

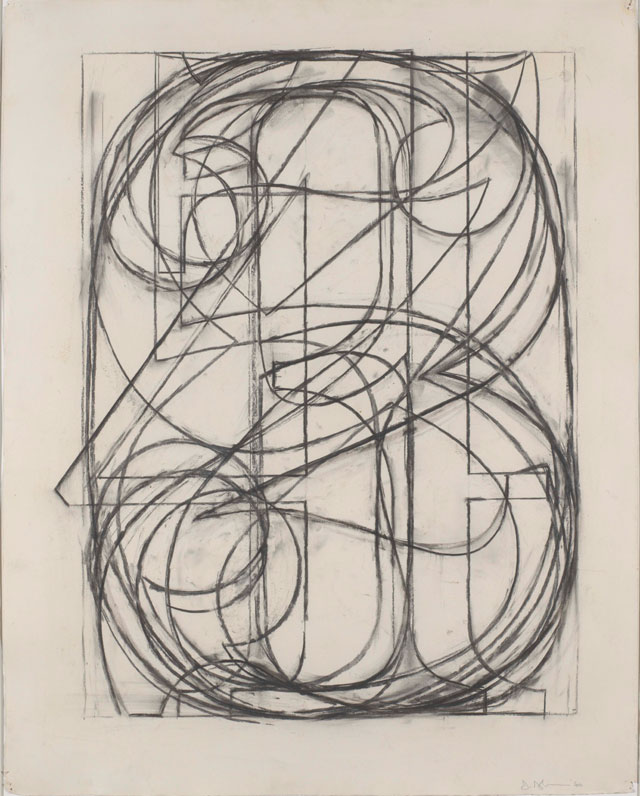

The blurring of the boundaries of art and life enabled Johns to find a potent form of the processing of self. A work such as Untitled (1972) is made up of three sections – marks drawn in paint that create an abstract pattern, referred to as “crosshatchings”, stones inspired by a wall, and a collaged panel using wooden struts with studio detritus attached. The alignment of the visual elements in this work seems incongruous, yet it evokes a sense of interlocking and connectivity, such as the weaving processes of traditional female craft processes. The crosshatching became the subject of the work. In doing so, it could be argued from a psychotherapeutic stance that Johns was working outside of a strict gender role, creating images that could, on one hand, illustrate a textbook on the psychology of visual perception, and, on the other, be seen to represent a very deep coming to terms with his abandonment by his parents, following their divorce when he was a two-year-old child. In 1973, he had stated that he wanted his work to move away from “an exposure of my feelings”. Then, in 1984, he expanded the view. “In my early work, I tried to hide my personality, my psychological state, my emotions. This was partly to do with my feelings about myself and partly to do with my feelings about painting at the time. I sort of stuck to my guns for a while, but eventually it seemed like a losing battle. Finally, one must simply drop the reserve.”1

[image4]

Johns’s late work grew out of his cross-hatching technique. The use of cross-hatching from the early-70s, was galvanised further in 1980 after he received a postcard from a friend, of Edvard Munch’s painting Self Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed (1940-42), one of Munch’s final such works before his death in 1944. The late self-portrait (Munch was almost 80) employed cross-hatching on the bedspread that alluded to solitude, as well as birth, death and sex. In this, his pivotal, haunting late work, Munch places himself between the grandfather clock without hands that signifies the passage of time that humans have no control over, and the door, that represents transitional states and the exit, death. In 1990, Johns described how the cross-hatched works, “become very complex, with the possibilities of gesture that characterise the material – colour, thickness, thinness – a large range of shadings that become emotionally interesting”.2

Johns titled his own work after Munch’s late masterpiece; his work of the 80s came to represent an increased sense of human mortality. A curious serendipity seems at play where Johns’s work is shown to be of seminal importance, particularly coinciding as it does with the forthcoming exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed, which is used as a lens to reassess Munch’s oeuvre (the exhibition runs from 15 November 2017 to 4 February 2018; then at the Munch Museum, Oslo, from 12 May to 9 September 2018).

[image3]

Further, Johns’s use of encaustic (or hot-wax painting) from the 50s gives the work an appearance of the embalming process. A number of his works in the 80s assume the theatrical wonderment of walking into an Egyptian tomb. The entrance motif was also used by British artists such as Alan Davie (1920-2014), in the dense grid-like structure Entrance to a Paradise (1949) and Entrance for a Red Temple No 1 (1960), and the abstract artist Robyn Denny (1930-2014), who used the entrance of a tomb or room to indicate transition to another dimension. The tomb entrance evokes associations with the womb, with the sexual act and with fecundity. A painting by Johns evokes a sacred experience and is essentially a primal act of worship. He juxtaposes roughly finished areas with elements of old master paintings, including Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, a demon from Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, the psychological insight of Munch and the formal structures of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. His work of the 80s addresses the abiding images of life, death and transcendence.

As Fiona Donovan aptly observes of two bodies of his recent work (from 2012) that include Regrets (2013) and the monoprint Untitled (2015), both sparked by a photograph of a dejected male figure: “While mournful and at times haunting, these pictures pulse with a formal economy and a generative lyricism. Animated by a vital and engrossing current, they offer some meaning just beyond reach. Disenchantment and beauty coexist without the impulse to resolve the contradiction between them. There is an intensity in these works that results in a brooding clarity that ultimately reaffirms the significance for Johns of change and growth over synthesis. This, rather than the photographs that triggered the works, becomes his subject.”3

It is important to be able to see this work in the flesh, for it reaffirms Johns’s stature as an artist and also helps us to understand the meaning of art that came to include household and studio objects and imprints with a naturalness and grace, as if art had always included the detritus of the studio, brooms, paintbrushes, fabric. There are many works in the Royal Academy exhibition that indicate just how familiar we are with aspects of art history, and particularly with postwar America and the manner in which neo-dada has been absorbed so completely into our aesthetic.

[image9]

The scholarly new Thames and Hudson monograph Jasper Johns: Pictures within Pictures, 1980-2015 by Fiona Donovan, published in the UK this month, is the first comprehensive book on Johns’s late painting, from the early 80s to the present. Based on the author’s conversations with the artist, whom she has known for more than 30 years, it elucidates the impalpable, at times paradoxical, nature of his career. Although the work of Johns has received extensive critical attention, the late period has not, until now, been adequately appraised. Donovan’s elegant monograph addresses this imbalance and it is one of the finest artist monographs to read and refer to over and over for its depth and inspiring observation of what art can still achieve.

Untitled (1998) in black on cream paper is made up of a cross and an eclipse of the sun, and a mass of tangled worshipful human beings. A ladder connects light with dark, and refers to enigmatic aspects of life. The imagery here is incorporated into Untitled (1992-94) at the Royal Academy. Johns’s depiction of darkness expresses a deep knowledge and insight of human archetypes and a response to the sacred with vast depth and originality.

References

1. Jasper Johns: Pictures within Pictures, 1980-2015 by Fiona Donovan, published by Thames and Hudson, page 67.

2. Ibid, page 67.

3. Ibid, page 17.