Jessica Carlisle Gallery, in association with Redfern Gallery, London

3 – 29 October 2016

& House of the Nobleman at 10 Park Crescent, London (ongoing project)

Throughout October 2016

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

“My definition of my art then, is one of mesmerising you to come and taste the honey” – Paul Feiler1

German-born, Paul Feiler (1918 – 2013) spent much of his long career in Cornwall where he became loosely associated with the abstract artists known as the St Ives painters, although he would eventually disassociate himself from this informal grouping.

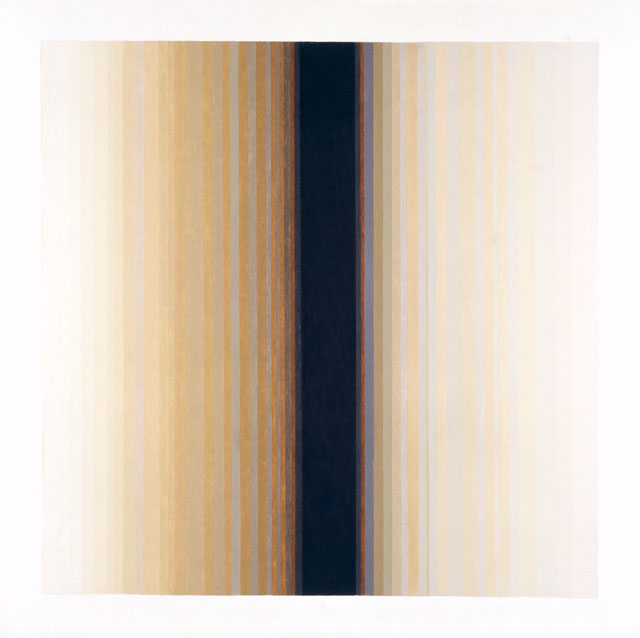

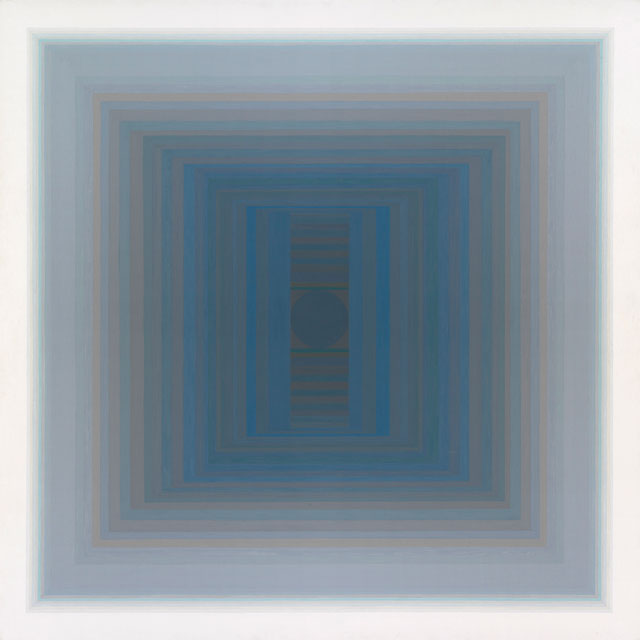

Initially, he experimented with the drab realism of the Euston Road School, before turning his eye to the Cornish seas, cliffs and stones, gradually prising his images free of any figurative association. The definition of abstraction is wide-ranging, not to say contested, and Feiler worked though various versions of it with singular purpose, his initial subjects ranging from the movement and architecture of the railways to the space exploration of the 60s. His earlier works were freer, more textured and gestural – a colleague compared him with Nicolas de Staël, of whom Feiler was not yet aware. Teetering between the figurative and abstract, the tactile materiality and corroded tones of the 50s and 60s later transmuted into considerably more geometric, structured works consisting of perpendicular and rectangular matrices enclosing circular inner spaces on a square background. Examples of these signature works that occupied Feiler from the 70s for the rest of his career are currently on display in London, in a dedicated exhibition at the Jessica Carlisle Gallery, and alongside other modernist works at the Park Crescent site.

A numinous state is partly evoked by the titles Feiler gave to several sub-series of this oeuvre. Aduton andAdytum, for example,are inaccessible inner sanctums of classical temples, while Janiconrefers to Janus, the two-faced god of doorways and states of transitions, suggestive of the waythese works draw the viewer in, while at the same time irradiating outwards. Although chiefly composed of stripes, there is nothing hard-edged about these images, Feiler having stated that he hoped that, if he were remembered for anything, it would be “the ability to make a sharp edge look soft”.2 This quivering, luxuriant softness is effected through alluringly modulated arrangements of colour, ranging from cool blues and greenish-greys, to rusts, dusky umbers and blacks, in the subtlest of transitions from one to the other. In addition to the thin glazes of paint, Feiler incorporated gold and silver leaf into some works, enhancing the works’ icon-like quality, the occasional craquelure of the iridescent metals providing a vestige of the tactility of his earlier pieces.

In a later series, also represented at these exhibitions, Feiler experimented with the square relief, his name incidentally being a palindrome of relief (Feiler-Relief). These works, poised between painting and sculpture, are more reactive to their surroundings than the shrine-like canvases. In addition to gouache and metal leaf, they exploit Perspex as figure, ground and frame, a material to be seen and seen through, literally as well as visually projecting and receding.

The optical and phenomenological effects of Feiler’s immersive, magnetic portals recall the transcendent geometric abstractions of certain European constructivist, concrete and kinetic currents that re-emerged in the 60s. British modernist experiments had, of course, been affected by the arrival in England of first wave constructivist émigrés such as László Moholy-Nagy and Naum Gabo in the 30s, the latter having also spent time in St Ives. As with other artists working in a constructivist-concrete vein, Feiler’s arrangements of rational, geometric forms yield curiously otherworldly sensations and suggest the tension between what the eye perceives and the brain imagines.

A perceived peril of abstraction was that it would be judged “merely” decorative, anathema to most modernists, from Kandinsky and Mondrian to Frank Stella. This hazard increases in the Park Crescent setting, given that Feiler’s works there adorn the walls of luxury apartments for sale decked out in cloyingly bland corporate “chic”. When Mark Rothko visited Cornwall in 1959, where he met Feiler and other adherents of the St Ives group, he strongly rejected the notion of decorative serenity in his abstract art: “You think my paintings are calm, like windows in some cathedral? You should look again. I’m the most violent of all the American painters. Behind those colours there hides the final cataclysm.”3

Whether Feiler’s consummate, spectral irradiations induce quietude or malaise is, naturally, dependent on individual response (he reported both reactions on the part of viewers). They do not convey Rothko’s apocalyptic vision, but their optical purity and hypnotically auratic presence are indisputably more than “merely” decorative, and fully capable, as Feiler intended, of mesmerising viewers into tasting the honey.

References

1. Paul Feiler, interview by Michael Tooby, in Paul Feiler: Form to Essence: Theme and Development, An Exhibition at Tate Gallery St Ives, 1995 - 1996.

2. Ibid.

3. Mark Rothko’s visit, 1959, http://www.michaelcanney.co.uk/Rothko.html