BOZAR, The Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels

29 January – 25 May 2014

by JULIE BECKERS

As curator Ignacio Cano Rivero explains in the ambitious catalogue that accompanies this exhibition, Zurbarán did not enjoy the same artistic success and fame as the court portraitist Velázquez. However, the native of Extremadura did possess something remarkable. A devout Catholic strongly influenced by the Counter-Reformation and the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, Zurbarán had the ability to put across a clear, direct and easy message in his paintings.1

The result of this spirited approach culminates in an oeuvre that is predominantly made up of work with religious subject matter. Zurbarán, with an apparently tender – yet at times haunting – brushstroke, easily conveys his personal devotion in scenes from the lives of saints, martyrs and monks, often commissioned by the very characters he depicted in the monasteries and the church.

Contextually, an understanding of the Council of Trent (1563) concerning the visual arts brings the viewer closer to Zurbarán’s work. Through the decree On the Invocation, Veneration and Relics of Saints and On Sacred Images, the council asserted that images were to provide examples for the faithful to live by. Images should instruct rather than lead toward false dogma or superstition. They were to be simple, direct, moving and encourage devotion.2

Painters of the time necessarily adapted their work and hence responded to the council. Zurbarán’s paintings, albeit a century later, visualise these mid- 16th-century guidelines. Simple, yet strikingly direct, the Spaniard developed, to quote Rivero, “a unique visual language in which he combined pure naturalism with a poetic modernity”, which is evident from the early paintings, which hint at a Caravaggesque influence marked by the dramatic use of chiaroscuro, to his late, more personal and poetic paintings.3

With this exhibition, BOZAR offers an occasion to celebrate Zurbarán 350 years after his death, as well as adding to the master’s wider public appeal. The artist proved a hit in 2009-10 during the National Gallery’s exhibition in London, The Sacred Made Real, where one of Zurbarán’s famous Christ on the Cross paintings took centre stage. By looking beyond the paintings and offering the visitor a true gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), the dark grey tones of the exhibition rooms at BOZAR, the presence of the almost frugal 17th-century music by, for example, Manuel Machado, the ascetic visuals of monks and sweet little lambs, the museum, tries its best to give the viewer an adequate contextualised idea of Zurbarán’s work.4

Spread over a U-shaped exhibition space, 12 separate rooms chronologically explore Zurbarán’s career. The display contains an unprecedented set of pieces selected from the most prestigious international collections, both public and private. Four newly identified paintings make their debut here and a further six have been extensively restored before being put on display. The space, through several turns in corridors, cleverly leads the viewer to four different points where a “stellar” piece can be contemplated. The dramatic lighting and dark colours aided by little “music hubs” help the visitor imagine a period eye.

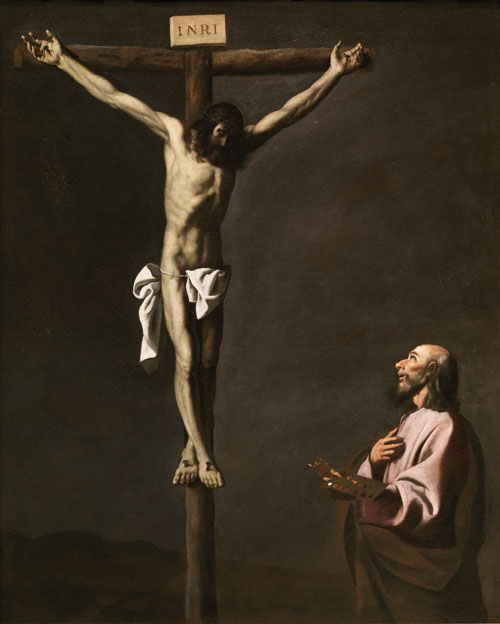

The first rooms focus on the artist’s early career, when he signed his initial contract in Seville (1626) with the Dominican monastery of San Pablo el Real for 21 paintings depicting the life of Saint Dominic. Zurbarán’s most important commission, for the monastery of the Shod Mercedarians in Seville in 1628, sealed his reputation as an artist; Saint Peter Nolasco’s Vision of 1629 is proof of his early style. Here, there is dramatic use of light and colour while the background remains unadorned, pushing the key elements of the iconography to the foreground. Zurbarán repeats this with his 1635 depiction of Saint Francis in Meditation, one of the stellar pieces. An anonymous Francis is set against a dark background, head down, battered hands caressing a human skull; a painting that is made to instruct and to move, not to admire nor to please. Another showstopper is the rather sweet Agnus Dei of 1635-40. A theme close to the artist’s heart shows the Lamb of God, legs tied, against a dark background, probably emulating the suffering Christ, a topic Zurbarán kept visualising throughout his career in his pictures of Christ on the cross.

In 1634, Zurbarán was summoned to court to work on the decoration of the Palacio del Buen Retiro in Madrid, probably with the help of Velázquez. It is evident in these rooms filled with portraits and paintings that emulate mysticism in everyday life that Zurbarán felt somewhat lost, and less convincing, painting in this entirely different genre.

The painter regains clarity in the 1630s when he commits to depicting an entire collection of Marys, including the famous Immaculate Conception of 1630, for the city of Seville. The most impressive work of this type was conceived in 1638, when Zurbarán was commissioned to paint The Virgin of the Rosary Venerated by Carthusians for the monastery of Santa Maria de la Defensión in Jerez de la Frontera. This piece is, without a doubt, the most impressive of the exhibition and Zurbarán’s most ambitious and monumental work.

It has been noted by some that Zurbarán’s later work lacks conviction. With the economic decline of Seville in the 1640s, artists were forced to produce work catering to a cheaper market and perhaps in doing so had to betray their convictions. Zurbarán also fell victim to this trend, as can be seen in his paintings for the New World. Although beautifully rendered, the spirit of the younger Zurbarán seems lost.

Yet at the end of his artistic career, and that is why this exhibition is more than worthwhile, the Spanish master leaves a lasting impression. Before his death in 1664, Zurbarán returns to two subjects that would both eternalise his reputation as a painter and summarise his oeuvre. A Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John and Saint Luke as a Painter, before Christ on the Cross. He depicts the Madonna with the same tender emotion he showed in the 1630s and leaves a powerful testament by presenting Saint Luke as a painter observing the suffering Christ set against the darkest of backgrounds. Autobiographical perhaps?

References

1. Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) by Ignacio Cano Rivero, published by BOZAR Books and Mercator, 2014, page 11.

2. Ibid, page 5.

3. Ibid, page 3.

4. BOZAR also organises a series of lectures, movies and guided visits on the Spanish master throughout the year.