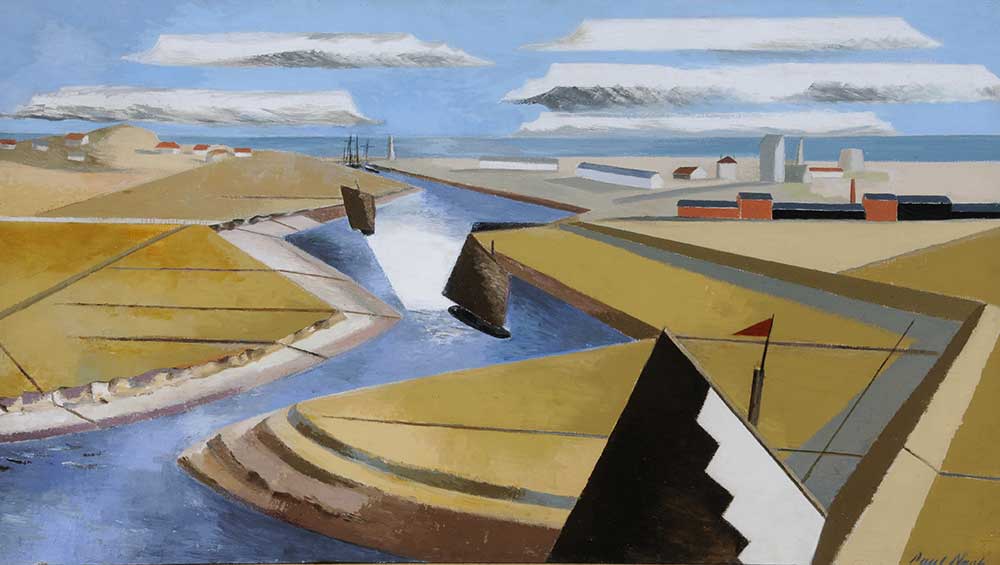

Paul Nash, The Rye Marshes, East Sussex, 1932. Oil on canvas, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull Museums, UK. © Ferens Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images.

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

12 November 2022 – 23 April 2023

by DAVID TRIGG

Boasting several areas of outstanding natural beauty, including the South Downs national park and more than 140 sites of special scientific interest, it is not hard to see why so many artists have been drawn to the particular qualities of the Sussex landscape. Bringing together an outstanding selection of work from the 18th century to the present day, including many rarely seen loans, Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood and Water at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester charts the manifold responses to this quintessentially English landscape, famous for its chalk-cliff coastline and rolling hills.

While the glut of works is by 20th-century artists, the show opens with significant 19th-century responses to the Sussex landscape by William Blake, John Constable and JMW Turner. Blake lived in the Sussex coastal village of Felpham from 1800 to 1803, a period that inspired a stunning series of wood engravings of rural scenes produced for an 1821 edition of The Pastorals of Virgil by Robert Thornton. Constable, an artist more commonly associated with Suffolk, also took a shining to Sussex, describing Devil’s Dyke as “perhaps the most grand and affecting natural landscape in the world”. His Seascape Study: Brighton Beach looking west (c1824-28) pits the grandeur of nature against human vulnerability with the inclusion of two windswept ladies watching the choppy sea beneath an expansive cloud-filled sky.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Chichester Canal, c1828. Oil on canvas. Tate: Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856.

The star here, though, is Turner’s large and atmospheric Chichester Canal (c1828), a full-size oil sketch commissioned by the artist’s great patron, the third Earl of Egremont. Turner was a regular visitor to Chichester and, given that 2022 is the 200th anniversary of Chichester Canal, its inclusion is fitting. Painted from the village of Hunston, the serene scene captures the tension between nature and industrial development; a tall collier ship on the water, which serves to symbolise evolving commercial interests, is echoed by the silhouette of Chichester Cathedral beyond, standing for the stability of tradition.

A spirit of experimentation saturates the exhibition, especially in the early rooms, where the Sussex landscape is presented as a site for British artists to experiment with international modernism. Take Robert Bevan, who was brought up in the village of Cuckfield, where, late in his career, he painted The Town Field, Horsgate, West Sussex (1914). His use of simple colours, chunky brushes and a palette knife to flatten elements of the farmland scene reflect the influence of Paul Gauguin, while an adjacent preparatory study, constructed from swarms of swirling pencil marks, recalls Vincent van Gogh. Bevan’s friend, Lucien Pissarro, who became a British citizen in 1916 and was a principal figure in the Camden Town Group, similarly experimented with modern styles, employing the techniques of impressionist and post-impressionist painters in works such as Cottage at Storrington (1911), painted en plein air using a pointillist technique.

Duncan Grant, Landscape, Sussex, 1920. Oil on canvas. Tate, bequeathed by Frank Hindley Smith, 1940. © Tate.

For the progressive Bloomsbury Group artists, Sussex provided a rural retreat from London’s smoggy streets, and there are two, almost identical views of the pond at Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s Charleston farmhouse, painted in a vibrant post-impressionistic style four years apart by the respective artists. Another artist with a country retreat in Sussex was William Nicholson, who bought a family home in Rottingdean, from where he would walk up into the South Downs.

William Nicholson, Whiteways Rottingdean, 1909. Oil on canvas board. Private collection. © Pallant House Gallery. Photo: Barney Hindle.

A selection of small canvases painted in a simple, minimalistic style capture the expansive landscape under different lighting conditions, including the perfectly balanced Whiteways, Rottingdean (1909), with cattle grazing on a hillside beneath wispy clouds.

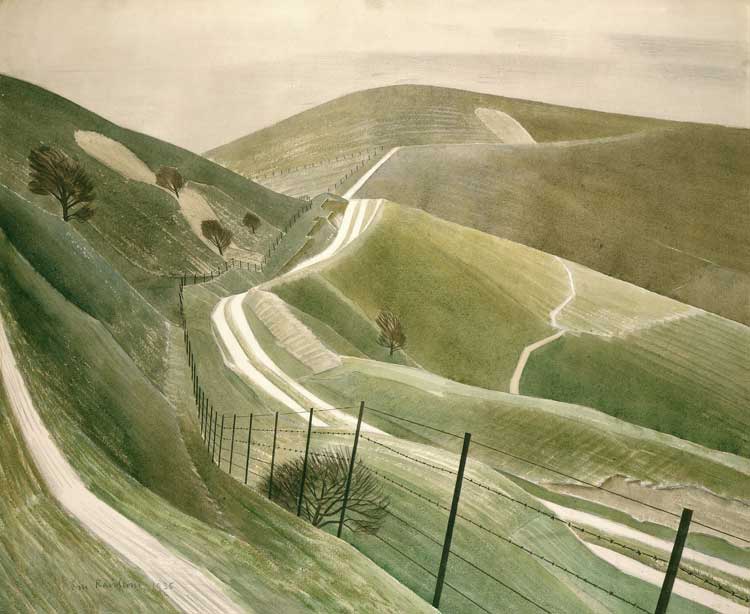

No exhibition on Sussex would be complete without the work of Eric Ravilious, who grew up in the area and whose elegant watercolours of the South Downs are synonymous with the county. Indeed, Chalk Paths (1935), with its lonely hills delineated by barbed-wire fencing and chalk striations, is a quintessential view of the Downs.

Eric Ravilious, Chalk Paths, 1935. Watercolour on paper. Private collection. © Bridgeman Images.

Ravilious lost his life during active service in the second world war. His works are displayed in a room with Charles Knight’s Ditchling Beacon (c1940), created as part of the wartime Recording Britain project, which saw artists on the home front documenting Britain’s threatened rural landscapes and architectural heritage. With the risk of invasion, Sussex was one of the earliest counties to be recorded, though Knight’s peaceful sun-drenched scene reflects nothing of the period’s fear and anxiety.

Ivon Hitchens, Curved Barn, 1922. Oil on canvas, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (Presented by the Artist, 1979), © Estate of the Artist / DACS.

The war drew many artists away from cities and into the countryside. Ivon Hitchens, who has several works in the show, including his hallucinatory Curved Barn (1922) and vibrant abstraction Sussex River, near Midhurst (1965), found a place of sanctuary in Sussex after the bombing of his London studio. Paul Nash, who was an official war artist in both world wars, moved to Rye in 1930, where he painted numerous coastal scenes, including The Rye Marshes, East Sussex (1932), an intriguing semi-abstract composition in which the landscape is transformed into a series of interlocking geometric shapes and flat planes of colour.

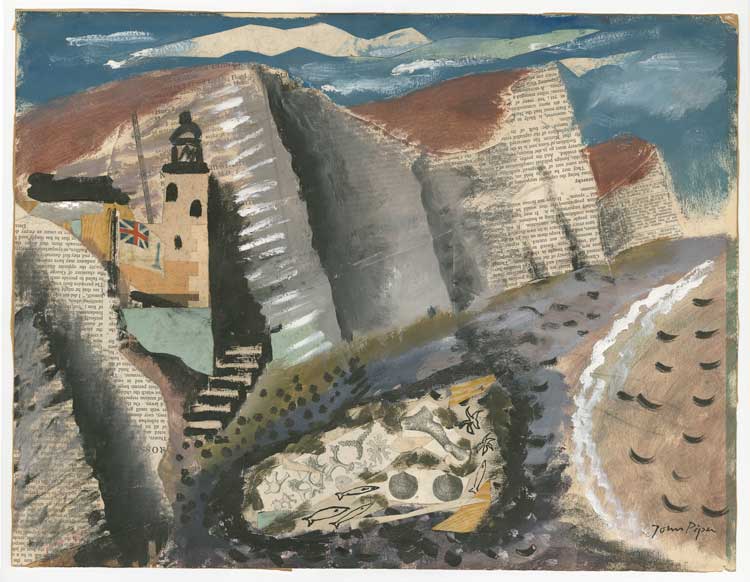

John Piper, Beach and Star Fish, Seven Sisters Cliff, Eastbourne, 1933-34. Gouache, pen and ink with collage of paper and fabric on paper. Jerwood Collection.

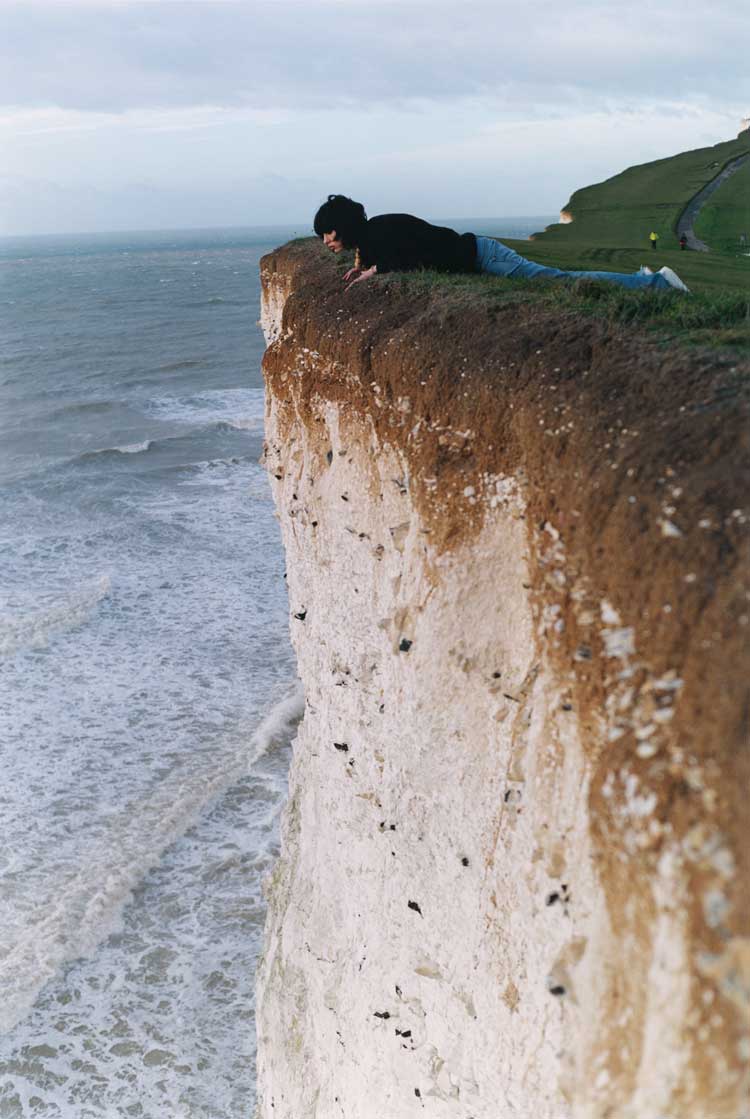

John Piper was also drawn to the coast. His collage Beach and Star Fish, Seven Sisters Cliff, Eastbourne (1933-34), in which the chalk cliffs are rendered using pages torn from the New Statesman, connect the ancient landscape to current affairs and the looming war clouds brewing on the continent. Similarly, End of Land I (2002) by the contemporary photographer Wolfgang Tillmans considers the connections between national identity and landscape. A figure peers cautiously over the edge of the Beachy Head cliffs, a sheer border between land and sea, England and Europe. Considering Tillmans campaigned vociferously against Brexit in 2016, this image has become newly charged with significance.

Susan Collins, Seascape, Pagham, 23rd November 2008 at 1731 pm, 2009. Digital inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photorag paper. Copyright the artist.

Among the many contemporary artists in the exhibition, including Tania Kovats, Jem Southam and Andy Goldsworthy, is Susan Collins, whose newly commissioned video work Dell Quay (2022) is replete with ideas relating to surveillance and the often fraught relationship between technology and the landscape. Images from a webcam set up at a small West Sussex harbour are transmitted to the gallery, but update incredibly slowly, over the six-hour span of a tidal cycle. Even though the image is “live”, this durational aspect, coupled with a low resolution, gives the work a painterly and meditative quality that slows down the looking process.

With more than 100 works by more than 50 artists, Sussex Landscape is generous and compelling, if at times a little unfocused. Virginia Woolf, writing in 1937, described the South Downs as “too much for one pair of eyes, enough to float a whole population in happiness, if only they would look”. There is certainly much to delight the eyes here, though, more than anything, the exhibition leaves you with the compulsion to get out of the gallery and into the landscape, to experience the chalk, wood and water for yourself.

Wolfgang Tillmans, End of Land I, 2002. Ink on paper. Towner Eastbourne. © Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London and Hove.